Excellent analysis in a comment: In one of the poorest headlined columns I have read, Mr. Williamson details some of the shenanigans of the leaders of the NRA, actions that might indeed run afoul of the Internal Revenue Service. But the column is not really about the NRA.

The column itself focuses on the overreach of New York Attorney General Letitia James in her attempt to ‘disband’ the NRA, a transparent attempt to inhibit their political agenda for 2020 and to continue its incessant attack on the Second Amendment.

This is, unfortunately, only part of the creeping activism of radical Attorneys General installed at state and city levels throughout the Blue States.

And it represents a dagger thrust at those people and corporations found out-of-favor with progressive aims, from climate change and clean power, to lax law enforcement, to single-payer health plans, to monitored and regulated ‘free speech.’

Williamson’s conclusion:

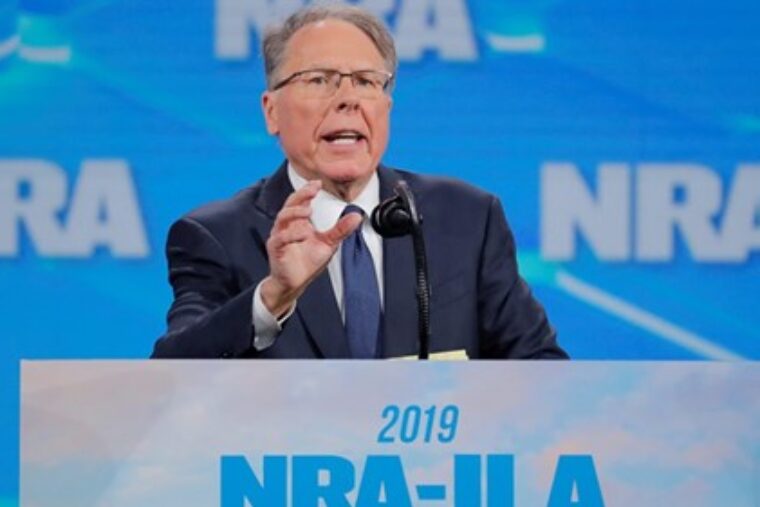

“What is going on in New York State is not about Wayne LaPierre’s bar tab or who pays for him to get from point a to point b in rock-star style. It is totalitarianism on the subscription plan, the slow emergence of a distributed police state whose headquarters is nowhere and whose jurisdiction is everywhere.”

Be afraid. Be very afraid.

And the rise of something sinister

Wayne LaPierre is not the first nonprofit high-roller.

One of the scandals of the 1990s that never quite got off the ground the way Democrats had hoped had to do with how much the Red Cross paid its CEO, at the time Elizabeth Dole, who had been labor secretary in the George H. W. Bush administration and was wife to then-Senator Bob, soon thereafter the 1996 Republican presidential nominee. The Red Cross paid Mrs. Dole $200,000 a year, or about $380,000 in 2020 dollars, a $15,000 bump over what it had paid her predecessor. She donated her first year’s salary as a goodwill gesture.

There was never any serious argument that there was anything improper about Mrs. Dole’s salary. But that kind of a paycheck just feels unseemly to certain people — mostly those who do not themselves make a lot of money and believe that they really should. In reality, nonprofits and charities compete in the same labor market as any other institution, and high-end executives cost a lot of money. The highest-paid nonprofit CEOs of 2017 (the most recent year for which the Economic Research Institute has reported data) were mostly (but not exclusively) executives in health-care systems, and they were paid salaries similar to what they would expect to earn as executives in for-profit health-care systems or banks: $21.6 million for the president and CEO of Banner Health, $12 million for the head of Carilion, $11.9 million for the head of Money Management International, a nonprofit credit-counseling operation funded by institutions that want debtors to pay their debts. (“Nonprofit” does not imply the absence of self-interest.) The CEOs of large ($1 billion or more in assets) nonprofit credit unions make on average about a million and a half bucks a year, and the best-paid of them (again as of 2017) took home $12.5 million in total compensation. As with their colleagues in for-profit banking, credit-union CEOs usually draw a relatively small salary but can earn a great deal of money in performance-based pay by achieving certain business goals.