Last October, Shaneen Allen, 27, was pulled over in Atlantic County, N.J. The officer who pulled her over says she made an unsafe lane change. During the stop, Allen informed the officer that she was a resident of Pennsylvania and had a conceal carry permit in her home state. She also had a handgun in her car. Had she been in Pennsylvania, having the gun in the car would have been perfectly legal. But Allen was pulled over in New Jersey, home to some of the strictest gun control laws in the United States.

Allen is a black single mother. She has two kids. She has no prior criminal record. Before her arrest, she worked as a phlebobotomist. After she was robbed two times in the span of about a year, she purchased the gun to protect herself and her family. There is zero evidence that Allen intended to use the gun for any other purpose. Yet Allen was arrested. She spent 40 days in jail before she was released on bail. She’s now facing a felony charge that, if convicted, would bring a three-year mandatory minimum prison term.

At first blush, much about Allen’s case seems counterintuitive. When we think about the gun control debate, we typically picture progressive pundits, politicians and activists arguing with white, conservative activists and politicians representing rural interests. When I first posted her story to Twitter, a couple of progressive responders predicted that because Allen is a black single mother, the gun rights community would all but ignore her. But that hasn’t been true at all. In fact, Allen has become something of a rallying point for gun rights activists. She is being represented by Evan Nappen, an attorney who specializes in gun cases and is a gun rights activist himself. Some conservatives have similarly accused progressives of ignoring Allen’s case because she stands accused of a gun crime. It’s certainly true that her case has received much more attention from the right than the left. But Nappen says he has seen plenty of support for her from racial justice groups, too.

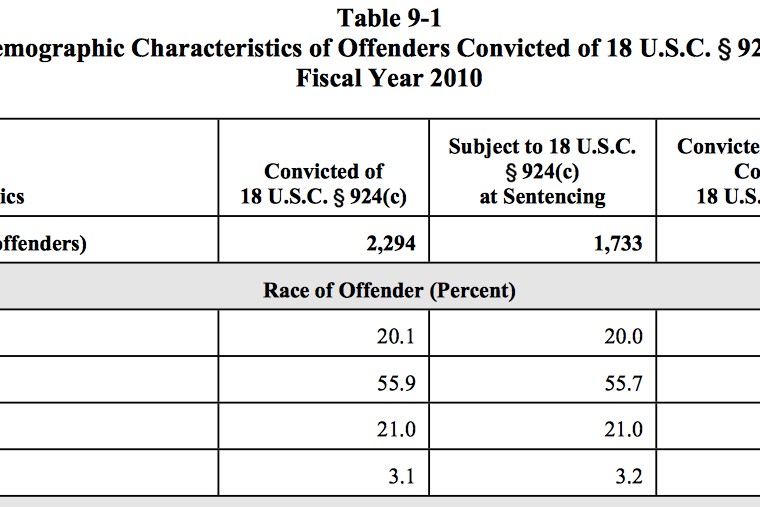

As it turns out, Allen’s case isn’t unusual at all. Although white people occasionally do become the victims of overly broad gun laws (for example, seethe outrageous prosecution of Brian Aitken, also in New Jersey), the typical person arrested for gun crimes is more likely to have the complexion of Shaneen Allen than, say, Sarah Palin. Last year, 47.3 percent of those convicted for federal gun crimes were black — a racial disparity larger than any other class of federal crimes, including drug crimes. In a 2011 reporton mandatory minimum sentencing for gun crimes, the U.S. Sentencing Commission found that blacks were far more likely to be charged and convicted of federal gun crimes that carry mandatory minimum sentences. They were also more likely to be hit with “enhancement” penalties that added to their sentences. In fact, the racial discrepancy for mandatory minimums was even higher than the aforementioned disparity for federal gun crimes in general:

Some on the law-and-order right will argue here that the disproportionate number of arrests, convictions and mandatory minimum sentences for black offenders is merely a reflection of the fact that black people are disproportionately likely to commit these sorts of crimes. Progressives will argue that the disparity reflects institutional racism in the criminal justice system. There’s some truth to both. But there’s no disputing the figures.

Much of this boils down to professional discretion. When a person victimizes another person with a gun, the offending person has already committed a crime. And in nearly every state and under federal law, it is already an additional crime to use or possess a gun while doing something that is already a crime. So when gun control advocates say we need to crack down on gun offenders, or when they propose that we create new gun crimes, they aren’t suggesting we crack down on people who use guns to rob banks or to commit murders. We already go after those people. What they’re proposing is that we target people who possess, sell or transport guns not because they want to hurt people with them, but for reasons ranging from what most reasonable people would believe to be justifiable (like Shaneen Allen) to what gun control proponents would likely consider objectionable (the gun shop owners and gun manufacturers who make money selling weapons).

If you’re an advocate for gun control, you could certainly argue that the tradeoff here is worth it. There’s an argument to be made that we still need to target irresponsible gun owners and gun merchants, even if they aren’t using guns to victimize people, because their guns could end up in the hands of people who do. But if you’re going to make that argument, you also need to understand that prosecuting people under these circumstances means that we’ll be putting more people in prison. And who those people are will reflect all of the biases, prejudices and predispositions present in the laws we already have.

It will also mean giving a lot more discretion to law enforcement officials and prosecutors. When someone robs a bank with a gun or kills someone with a gun, there’s no debate about who needs to be investigated and prosecuted. When a police agency is charged to seek out and prosecute people who are illegally possessing or transferring guns, they’re required to use their own discretion when it comes to what communities to target and what methods they’ll use to target them.

Inevitably, this will manifest as sting operations against communities with little political clout. (Or, just as troubling, deliberately targeting people for political reasons.) Just this week, an incredible investigation by USA Today reporter Brad Heath demonstrated just how this plays out in the real world:

The nation’s top gun-enforcement agency overwhelmingly targeted racial and ethnic minorities as it expanded its use of controversial drug sting operations, a USA TODAY investigation shows.

The Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives has more than quadrupled its use of those stings during the past decade, quietly making them a central part of its attempts to combat gun crime. The operations are designed to produce long prison sentences for suspects enticed by the promise of pocketing as much as $100,000 for robbing a drug stash house that does not actually exist.

At least 91% of the people agents have locked up using those stings were racial or ethnic minorities, USA TODAY found after reviewing court files and prison records from across the United States. Nearly all were either black or Hispanic. That rate is far higher than among people arrested for big-city violent crimes, or for other federal robbery, drug and gun offenses.

The ATF operations raise particular concerns because they seek to enlist suspected criminals in new crimes rather than merely solving old ones, giving agents and their underworld informants unusually wide latitude to select who will be targeted. In some cases, informants said they identified targets for the stings after simply meeting them on the street.

Heath points out that a federal judge recently accused the agency of “trolling poor neighborhoods” in search of patsies. In some cases, the ATF — the federal agency that exists to fight gun crime — actually supplied its targets with the guns the agents would then arrest them for using to rob stash houses — which were also set up by the ATF.

In April of last year, the Milwuakee Journal Sentinel reported that ATF agents in Milwaukee had set up a fake store front, then convinced a black man with brain damage to set up illegal gun and drug sales. They later arrested him for those crimes. At the time, the ATF told the Milwaukee Journal-Sentinel that the sting was an isolated incident. It wasn’t. The paper later discovered similar sting operations targeting minorities and mentally disabled people all over the country.

In the 1990s, gun rights activists accused the ATF of explicitly targeting people for their advocacy (with plenty of evidence to back their claims), often with violent and destructive raids on their homes. You needn’t be a Second Amendment purist to understand the implications of using the discretion that comes with enforcing victimless crimes to target people for their political views, any more than you need to be a racial justice activist to understand the injustice of using the same discretion and the same laws to primarily target people of color, people whose mental capacity makes them particularly susceptible to persuasion, or people who lack the clout or resources to defend themselves.

One could argue that the gun laws don’t need to be enforced in a racially discriminatory manner or in the catastrophically inept manner we’ve seen at the ATF. But you enforce the gun laws with the institutions you have, not the institutions you want. If we’re going to enforce gun laws that require discretion on the part of investigators and prosecutors — and add new laws to boot — we can only consider the demonstrated history of how investigators and prosecutors have used that discretion, not some idealized prosecutor or ATF investigator that we’d want to be in charge.

Discretion is a a big factor in the Allen case, too. According to Nappen, Atlantic County Prosecutor Jim McClain could have put Allen in a diversionary program for first-time offenders of victimless crimes that would have allowed her to avoid jail time. He didn’t. “Let’s remember, Shaneen Allen volunteered to the police officer that she had a gun and a permit,” Nappen says. “This isn’t something she was trying to hide. She didn’t think she’d done anything wrong. This was a victimless crime, and it’s just unconscionable that they’re putting her and her family through all of this. It could all be avoided.” Nappen says McClain has yet to give a reason for refusing to allow Allen into the diversionary program. McClain’s office did not respond to a request for comment.

The ATF is of course a federal agency. Shaneen Allen was arrested under New Jersey law. Nappen says he doesn’t know of any demographic data on gun arrests and prosecutions in New Jersey, but it’s an area of law in which he specializes, and he says by his estimate, the state figures probably mirror the federal data. “The institutional racism in our gun control laws is rampant. It goes back to the post Civil War era, when the laws were passed to keep black people and American Indians from arming themselves.” Nappen adds that the national gun control laws passed in the late 1960s were in response to racial riots taking place across the country. It’s a sentiment echoed by the progressive author and investigative reporter Robert Sherrill, who conceded in his book “The Saturday Night Special” that the laws were more about “black control” than gun control, and more recently in Nicholas Johnson’s just-published book, “Negroes and the Gun.” It’s also worth noting that the crime control policy most well-known, widely loathed and roundly condemned by racial justice activists — the New York Police Department’s stop-and-frisk policy — is at heart a gun control initiative. Its most high-profile champion is former mayor Michael Bloomberg, also a high-profile proponent of gun control laws like those in New Jersey.

Of course, none of this necessarily means that gun control advocates are wrong. It’s certainly possible that despite these flaws, a more robust system of gun control in the United States could net more good than harm. But make no mistake, more gun laws and more enforcement of victimless gun crimes will mean more people in prison. Those new prisoners will be disproportionately black and Hispanic. These realities need to be part of the discussion.

As for Shaneen Allen, Nappen says he is still hoping that McClain has a change of heart and allows her to enter the diversion program. If not, they will go to trial. Nappen says Allen is also protected by an amnesty period passed into law that allowed gun owners to surrender their weapons from August 2013 to February 2014 without fear of punishment. Whether Allen technically “surrendered” her weapon is a legal question. But if she is denied that defense, she will almost certainly go to trial, and under New Jersey’s gun law, she will have no real defense. Unless her jury engages in a defiant act of nullification, she will be convicted, and her trial judge will have no choice but to sentence her to the three-year minimum. At that point, her only hope will be to appeal to the New Jersey governor for clemency or a pardon. Current New Jersey Gov. Chris Christie commuted the sentence for Brian Aitken, whom Nappen also represented. Aitken’s case inspired a lot of outrage, but it didn’t result in any change in the law. So we’re back to discretion.

Discretion is a double-edged sword. Used properly, it can help avoid the unjust outcomes that will fall through the cracks when applying a uniform criminal code to a large population. But when enforcing victimless crimes, police and prosecutorial discretion can quickly become a tool of injustice, even of systematic oppression. Unless the laws like those in New Jersey are changed, people like Brian Aitken and Shaneen Allen will continue to be wholly at the mercy and discretion of police, prosecutors and governors —and thus subject to all the biases and prejudices of the people who hold those positions.

CORRECTION: This post originally identified Allen as a phlebologist. She is actually a phlebotomist.

by Radley Balko

https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/the-watch/wp/2014/07/22/shaneen-allen-race-and-gun-control/